You're here: MibSAR :: M-P Sourcebook Table of Contents :: Support

Free Emotional Support for Families with Missing Loved Ones

| << Prior Chapter | Next Chapter >> |

The resources listed below may be helpful for families dealing with the disappearance of a loved one.

Page contents:

- When Your Child Is Missing: A Family Survival Guide, by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), (NCJ 228735) Fourth Edition, 2010, 114 pages.

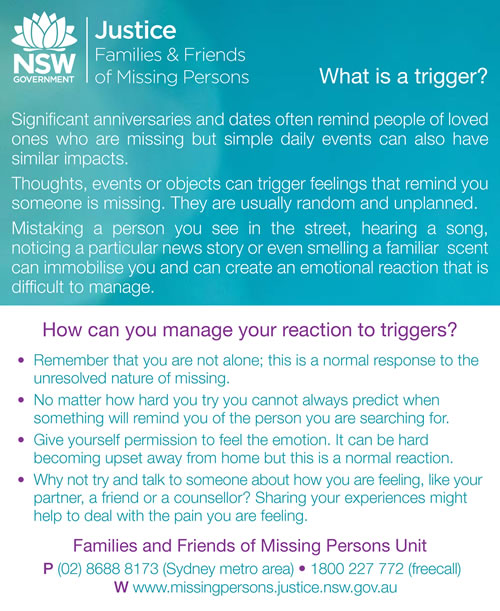

- What is a Trigger?, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia, 2 pages.

- Are you the parent of a sibling of a missing person?, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia, 2016, 2 pages.

- The SOS Guide: Missing Persons — A Guide for the Families and Friends of Missing Persons, by the National Missing Persons Coordination Centre (NMPCC), Australian Federal Police (AFP), 2017, 34 pages.

- Taking care of yourself when someone goes missing, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia, 2014, 2 pages.

- Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief, by Pauline Boss, First Edition, 2000, Harvard University Press, 176 pages.

- Missing People: A Guide for Family Members and Service Providers, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia, 2015, 35 pages.

- The Disappearance of an Adult in Criminal Circumstances: A Guide Intended for Relatives and Interveners, by Justine Razafindramboa, Association des familles de personnes assassinées ou disparues, (AFPAD), Quebec, Department of Justice, Canada, 2017, 32 pages.

- “Unending Not Knowing” — Lack of Resolution and Ambiguous Loss, excerpted from An Uncertain Hope: Missing People’s overview of the theory, research, and learning about how it feels for families when a loved one goes missing, by Missing People (MP) in conjunction with Same Cheatle (SANE, Macmillan Cancer Support), 2012, 2 pages.

- Living in Limbo: The Experiences of, and Impacts on, the Families of Missing People, by Lucy Holmes, Missing People, United Kingdom, 2008, 42 pages.

- A Child is Missing: Providing Support for Families of Missing Children, by Duane T. Bowers, LPC, National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), 2007, 56 pages.

- An Uncertain Hope: Missing People’s Overview of The Theory, Research, and Learning About How it Feels for Families When a Loved One Goes Missing, by Missing People in conjunction with Sam Cheatle (SANE, Macmillan Cancer Support), United Kingdom, 2012, 22 pages.

- In the Loop: Young People Talking About Missing, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia, 2015, 32 pages.

- Acknowledging the Empty Space: A Framework to Enhance Support of People Left Behind When Someone is Missing, by Dr Sarah Wayland, Australian Federal Police (AFP), 2019, 42 pages.

- Families of Missing Adults: Finding Help, by Ontario's Missing Adults (OMA), Department of Justice Canada (DOJC), 2015, 22 pages.

- Missing Kids (MK) is Canada’s missing children resource centre

- National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs)

- Missing People (MP)is a United Kingdom charity

- The Wisconsin Clearinghouse for Missing and Exploited Children and Adults (WCMECA)

- National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC)

- Jacob Wetterling Resource Center (JWRC)

- Missing Children Society of Canada (MCSC)

- Missing: A Guide for Families and Friends of Individuals with a Mental Illness Who Have Gone Missing, by Christine Lafond, Stephanie Scherbain & Gita Sud, Mental Health Education Resource Centre of Manitoba, Canada, 2006, 36 pages.

- Reconnecting when a missing person is located, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia, 2012, 2 pages.

- What happens when a missing person is located deceased?, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia, 2012, 2 pages.

|

|

| When Your Child Is Missing: A Family Survival Guide, by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) |

Personal and Family Consider-ations

Not knowing where your child is or how he or she is being treated is one of the hardest things you will have to face. One minute you will feel a surge of hope, the next, a depth of despair that will threaten your very sanity.

Life will become an emotional roller coaster that won’t really stop until you can hold your child in your arms again.

As you enter more deeply into the situation, know that you are not alone. Unfortunately, other families have had to travel this path and have experienced the same emotional wringer.

Families can and do survive — and yours will, too, but it will take all the strength, hope, and willpower you can muster.

Regaining Your Emotional and Physical Strength

Your ability to be strong and to help in the search for your child requires that you attend to your own physical and emotional needs. Although it may be hard right now for you to maintain your daily routine, it is paramount that you do so.

The driving force behind the search effort is you, and therefore you must, for your child’s sake, be physically and mentally well in order to handle it. The fact is, the nightmare will continue until your child is found, so you need to take as many breaks from it as you can.

Force yourself to eat and sleep.

Your body needs food and sleep in order to endure this ordeal. Although eating and sleeping may seem incredibly difficult, you must try. If eating regular meals feels like too much of a drain or if it brings back painful memories of your child, change your meal times and locations.

If you cannot sleep at night because you are nervous, tense, or afraid of night- mares, find a place to relax and nap during the day. Just make sure you are doing every- thing you can to take care of yourself.

Find time for physical exercise.

Any type of physical activity, even walking the dog, can help to ease the stress on your body and clear your head. Physical exercise also can help you relax at night so your body gets the sleep it needs.

Create space for yourself.

Find a place of refuge — away from the pressure of the search and the investigation — where you can be alone with your thoughts and regroup. Even a few quiet minutes can significantly relieve stress. It may help to walk in the park, visit your church or synagogue, or talk to a neighbor.

Try to take as much time as you need and can spare. Remember that you are the best judge of what will help you to handle the life crisis and that it is okay — even necessary — to take a break from the stress for dinner and a walk.

Find ways to release your emotions.

Your emotions will be running wild and will seem out of control. In these circumstances fear, anger, and grief can take over your entire existence. Therefore, you need to find a way to release your emotions because if you can- not express them, you may find yourself taking it out on others.

Talk with someone — a friend, a relative, or a professional therapist — who will just listen. Also,

try to stay busy. You can cook, write letters that express your feelings without mailing them, or record your thoughts and feelings in a journal.

Keep a journal.

Some parents find it extremely helpful to keep track of their thoughts and feelings in a journal. Journal entries, which can be written or tape recorded, need not be coherent or intelligent. Their purpose is merely to record your thoughts and feelings at any particular time and to help you resolve them.

Put your anger and grief to work for you.

Come up with ideas for the search. For example, you can make a list of all of your child’s friends, neighbors, and acquaintances — anyone who might hold a clue as to the whereabouts of your child.

You can make a list of places your child frequented or even occasionally visited — anywhere law enforcement could look for your child. Finally, you can think of ways to release your emotions in a productive manner.

Stay away from alcohol and harmful medications.

Alcoholic beverages, harmful drugs, and even prescription medications can prevent you from being an effective member of the search team and can even induce depression.

However, if you are having trouble sleeping at night or coping during the day, ask your physician for help. He or she may prescribe a medication that will help you sleep or alleviate your depression. Just be sure that you only take medications under the supervision of a physician because some can be addictive.

Don’t blame yourself.

Looking back, you may feel that there was something you could have done to have prevented your child’s disappearance. You can literally drive yourself crazy asking, What if . . . ?

But the fact is, if you did not arrange for the disappearance, you should not hold yourself responsible for not knowing or doing something that may seem obvious in hindsight. And remember, children have been abducted out of the safety of their own bed- room while their parents slept in the room next door.

Don’t shoulder the blame of others.

Recognize that some people may blame you for the disappearance because of their own fears for their children. They may imply that if you had watched your child more closely, he or she would not have disappeared.

Blaming you may make them feel somewhat safer in the world because they hold you — and your supposed mistake — responsible for your child’s abduction, rather than the abductor. Also, some- times one spouse blames the other for the disappearance of the child.

This is hardly ever fair and can critically harm the well-being of the entire family. Try to stay out of the blame game by being kind to yourself and to one another. Understand that sometimes anger and blame are irrational and misplaced.

Keep the lines of communication open among family members. If necessary, seek professional counseling or other outside assistance to help you handle the situation.

Stay united in your fight to find your child.

Don’t allow the stress of the investigation to drive a wedge into your family life. When emotions run wild, be careful that you do not lash out at or cast blame on others. Instead, give each other lots of warm hugs to counteract the stress inherent in the situation.

Remember that everyone deals with crises and grief differently, so don’t judge others because they do not respond to the disappearance in the same way you do.

Allow the opinions of other people to be their business, not yours.

Some people need to have an opinion as to how well you are handling the situation and whether you should be acting differently. Keep in mind that such judgments are merely the opinions of others and that at any given moment, you are doing the best you possibly can.

Seek peer support for yourself and your family.

Some parents find talking with other parents of missing children to be extremely beneficial. Sometimes it is enough to know that you are not alone and that someone else in the world truly understands.

Consider contacting one of the parent authors of this Guide (listed in the back of this book) or a member of Team H.O.P.E. (866–305–4673) for personal support (see page 79). Call the Child Protection Division at the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U.S. Department of Justice (listed in the Additional Resources section of this Guide), to get in touch with any one of the parent authors.

You can also ask your law enforcement contact for a list of victim’s advocates and local support groups. Nonprofit agencies or your state missing children’s clearinghouse can also provide you with the names and phone numbers of parents who can help.

Seek professional counseling for yourself and your family.

Nobody should have to live through the pain that you are going through. Professional counseling can be extremely helpful for parents and families to assist them in coping with their feelings of fear, depression, grief, isolation, anger, and despair.

You may think that you and your family can or should get through the crisis alone, but you don’t have to. Encourage family members to take care of themselves by seeking support and counseling. If you need assistance finding or paying for counseling, contact your local mental health agency or provider or ask another family member or friend to do this for you.

If you are uncomfortable with professional counseling, consider another form of support — from your clergy, a physician, a lay counselor, or a friend.

Seek peace and solace for yourself.

Many parents find comfort in their faith and use it as a powerful incentive to survive. The loneliness of grief diminishes somewhat for people who believe that they are not alone. Turning to — or returning to — religion can give parents the support and encouragement they need at this critical juncture in their lives.

Mentally Preparing

for the Long Term

As heartless as it may seem, your life and the lives of your children must go on. Although moving on with your life may seem impossible, you must do it — for the good of yourself and your family.

You will, of course, find that there is no such thing as “normal” life as you once knew it. Everything has changed, and has changed forever. And whatever the out- come, you will be dealing with this in some way for the rest of your life.

Going back to work is not abandonment of your child.

If you need to return to work, you may feel extremely guilty. Try to remember that your child must have a home to return to and that you are working to provide that home for your child. When you return to work, find a quiet place where you can go to be alone or to cry.

Your grief is likely to come unannounced, and you will need a place where you can express it. If your job requires a lot of concentration, which you are not able to give, look for another position that does not place as many demands on you.

The American Hospice Foundation publication Grief at Work, listed in the Recommended Readings and Other Resources section of this Guide, has additional advice.

Focus on your emotional well-being.

To keep yourself on a more even keel, continue individual and family counseling, and try to stay busy. You can immerse yourself in activities with your other children or volunteer to help in school, church, or the community. Don’t isolate yourself.

Many parent survivors try to help other parents by working through missing children’s organizations or by starting a group of their own. The books and articles listed in the Recommended Readings and Other Resources section of this Guide have proven to be particularly helpful.

It’s okay to laugh.

A laugh can be as cleansing as a good cry. Laughter not only helps to release tension and emotion, it helps to restore normalcy to life and it can also help the siblings of the missing child.

Never stop looking.

You will probably want to dedicate part of each day to your missing child. Use these hours to keep the search going and to keep the hope alive. You can set aside time to make phone calls, write letters, contact law enforcement, or do whatever you think will help in the search for your missing child.

Helping Your Other Children To Regain Their Physical and Emotional Strength

Your other children need your physical and emotional support now more than ever, but you may not be able to satisfy their needs. You may have barely enough energy to keep yourself going. You may feel that you are abandoning your lost child if you are not doing something every moment to find him or her. These are normal feelings.

Consider getting additional support for your other children during this time of crisis. Get a copy of What About Me? Coping With the Abduction of a Brother or Sister. This publication is available at www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/217714.pdf. Here are some ideas.

Find a safety zone for your children.

Find a safe place away from your home where your other children can be shielded from both the search effort and the media. This is especially important for young children, who still need to play and be themselves.

Trusted friends and relatives can provide a reasonably normal, nurturing life for your children in a relatively stress-free environment, so this is a good time to let members of the extended family and friends assume a large part of the responsibility for their care.

Just remember to maintain contact with your children — both over the phone and with regular visits — and to reassure them frequently how much you love them.

Consider letting your other children participate in the search along with an adult.

If it seems appropriate, you can allow your older children to actively participate in the search effort. However, it is important to consider their age, desire, and level of maturity and to respect their right to say no.

If your children are young, you will need to decide how much information you want revealed and whether it is appropriate for them to participate in the search effort. In some cases, younger children have distributed balloons and fliers.

If you decide to let your children participate, keep a gauge on how well they are handling the situation and be prepared to make changes, if necessary. Remember that there are both emotional and security issues to consider when your children participate in the search effort. Ask your law enforcement contact for advice.

Think twice about letting the media interview siblings.

Interviews with the media can be extremely traumatic to the brothers and sisters of a missing child. Children are seldom prepared for the extremely personal or probing questions asked by insensitive or pushy media personnel.

Remember that the media can and will be persistent, particularly given the sudden ascension of your family to “celebrity” status. Make sure that you supervise interviews and continue to set boundaries that are in your children’s best interests.

Bring the needs of your other children into balance with those of your missing child.

Focus on the needs of the children who are still at home. Remember that they, too, are trying to cope with their loss. Talk with your children about their feelings of fear, anger, hurt, and loss. Make them feel as important to you as your missing child.

Encourage them to return to the interests and activities they enjoyed before the disappearance — by playing with friends, participating in sports, or playing music.

Establish different routines to help your family cope.

Family meetings can be an effective way to deal with the changes wrought by the disappearance. They offer family members a safe, nonjudgmental environment in which to voice feelings of fear, anger, and frustration.

They also give family members an opportunity to keep one another informed about the ongoing investigation and involved in family decision making.

Celebrate birthdays, holidays, and other special events.

Young children will want to celebrate birthdays and holidays even when a brother or sister is missing. Plan ahead so you are not caught off-guard by the intense emotional roller coaster that can accompany such events.

You can, for example, try changing family holiday traditions and beginning new ones. Instead of throwing a big birthday party, you can eat cake and ice cream for breakfast and then open presents. If you have older children, instead of the traditional Christmas or Hanukkah celebration at home, you can go on a trip and celebrate there.

Remember that your children need to have fun and that they want you to celebrate, even if your heart is not ready for it. Recognize, however, that you have personal limitations as to what you will be able to handle and that those limitations need to be respected. The secret is to plan ahead.

Allow all members of the family to talk about your missing child, about their emotional reactions to the situation, and about their loss.

Don’t let the absence of your child and your deep sense of loss become a taboo subject. Instead, let your children know that they can freely express their thoughts and feelings to you and that they will be met with love and acceptance.

Let your children know that it is okay for everyone in the family — including mom and dad — to cry and that you can help each other by holding hands, giving each other a big hug or kiss, or getting each other a glass of water. Remember that even if you do not communicate with your children about your missing child, other children in the neighborhood will.

Don’t be surprised if your other children’s behavior drastically changes.

Everyone in the family has suffered a tremendous shock. In these circumstances, bedwetting, stomach-aches, depression, anger, sullenness, quietness, and truancy are common reactions.

But by the same token, don’t be alarmed if your child’s behavior changes very little or not at all. Children, just as adults, react differently to the disappearance of a child.

Help your other children return to some type of normalcy by returning to school.

Your children need the normalcy that the daily routine of school provides. But before your children go back to school, talk with them about what they want others to know.

Make sure they understand that most people in your community already know what has happened. Listen to your child’s thoughts and feelings about returning to school. Then, talk to your child’s teachers and counselors to help them prepare for the return of your child.

Ask the school to bring counselors into the classroom both after the disappearance and when your child returns to school.

Teachers and classmates of a missing child will also experience fear and grief. When your other children return to school, they and their friends — and the friends of your missing child — are bound to feel scared.

Ask your law enforcement contact if an officer can go to the school to teach the children both how to recognize dangerous situations and how to get away. Ask teachers and counselors for their help in giving all of the children the support they need to deal with this crisis.

The American Hospice Foundation publication Grief at School, listed in the Recommended Readings and Other Resources section of this Guide, has additional advice.

Ask other children who have faced similar difficulties to provide one-on-one support to your children.

A number of sources can put you in touch with other families that have experienced the trauma of a missing child.

Try calling your local law enforcement agency, your state missing children’s clearinghouse, NCMEC, or other missing children’s organizations.

Your children may be more comfortable talking with a peer who has gone through a similar ordeal.

Seek professional counseling for your children.

Your children are suffering just as intensely as you are and may need help dealing with feelings of fear, anger, and grief.

Don’t feel guilty that you cannot be their total support at this point in your life. Instead, look to others to help your children cope with the powerful emotions that follow the disappearance of a brother or sister.

Helping Extended Family Members To Regain Their Physical and Emotional Strength

The disappearance of a child affects many people — grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins. They, too, will experience deep emotional scars from the sudden loss. All of you will need the love and support of one another.

Extended family members can do a number of things — contribute to the search effort, take care of other children, or stay in close phone contact — to help them work through the pain and grief of losing a relative.

If possible, include extended family members in the search effort.

Extended family members can serve a variety of functions — as spokesperson for the family, coordinator of media events, coordinator of volunteers, or coordinator of searchers.

They can also develop and disseminate posters and fliers, contact missing children’s organizations to request assistance, and gather information to give to law enforcement to help in the search and recovery effort.

Put a daily report on your home answering machine or voicemail greeting, or Web site, to keep family members informed of progress in the search.

Law enforcement should keep you informed about the investigation, but in many cases extended family members are left out of such discussions. They may, as a result, feel left out and unsure of what to do.

Putting simple messages on your home answering machine or voicemail greeting, or Web site, will keep distant family members informed. It also will save you time from having to make or receive phone calls and in the process will help to free up your telephone line in the event that your child or someone with a tip is trying to get through.

Don’t try to provide emotional support to everyone in your family.

It is not your job to be an emotional “rock” for the extended family.

Instead, encourage family members to seek support and comfort from friends and other family members, from their church or synagogue, or from local mental health agencies, professional counselors, or other community resources.

Let members of your family know that you are depending on them to help you through this ordeal.

A Word About Starting a Nonprofit Organization

As time passes and your child does not return, you may become very frustrated. You may want to find a way to maintain or increase the level of activity. Some parents think about establishing a nonprofit organization (NPO).

An NPO must have a broad public purpose (that is, it cannot be devoted to a single child). Although state regulations vary, federal regulations are in place to assure the public that their contributions are well managed and are used for the organization’s stated purpose.

There are several things to consider when establishing a tax-exempt NPO:

- You need a purpose or mission statement, articles of incorporation, bylaws, an operating budget, and a board of directors. You will need to file necessary documentation with appropriate state and federal agencies.

- You must be aware of the differences between for-profit and nonprofit organizations to maintain the NPO’s programmatic and fiscal health.

- You need to keep meticulous files, including financial and corporate records. These records are open to the public. You may also have to meet the standards of charitable watchdog agencies.

- You may want to have an existing NPO serve as your fiscal agent.

- You will need to develop a program that attracts enough interest and financial support so it can be maintained.

A word of caution: Imagine yourself undergoing the worst possible trauma and deciding that NOW would be a good time to start a new business.

The startup and maintenance of a nonprofit organization can be incredibly challenging. Make sure you are surrounded by trusted friends or family who can do the majority of the work, especially at the beginning.

Key Points

- Force yourself to eat, sleep, and exercise. Realize that your ability to be strong and to help in the search for your child requires that you attend to your own physical and emotional needs. If you have trouble sleeping at night or coping during the day, ask your physician for help.

- Stay away from alcohol, drugs, and harmful medications, which can prevent you from being an effective member of the search team and can even induce depression.

- Find productive ways to release your emotions, such as keeping a journal, talking with a friend, taking a walk, exercising, cooking, cleaning, or thinking up ways to extend the search. Don’t isolate yourself.

- Don’t blame yourself for your child’s disappearance or allow yourself to shoulder the blame of others. Treat yourself and others as kindly as you can.

- Don’t feel guilty if you need to return to work. Remember that you are working to provide a home for your child to return to.

- Stay united with your spouse in your fight to find your child. Don’t allow the stress of the investigation to drive a wedge into your family life, and don’t misjudge others because their response to the disappearance is different from yours.

- Don’t allow the absence of your child and your deep sense of loss to become a taboo subject. Encourage open discussion of feelings in a safe, caring, nonjudgmental environment during family meetings.

- Establish different routines for daily life and for celebrating birthdays, holidays, and other events. Find a safe place away from your home — perhaps with friends or relatives — where your other children can feel free to play and express them- selves, away from the spotlight of the search and the media.

- If it seems appropriate, allow your other children to participate in the search, perhaps by distributing posters, fliers, or balloons. Remember that both emotional and security issues need to be addressed.

- Don’t be surprised if your other children’s behavior changes drastically. Bed- wetting, stomachaches, depression, anger, sullenness, quietness, and truancy are common reactions. But remember that children, just like adults, react differently to the disappearance of a child, and some may not show any change in behavior. Get a copy of What About Me? Coping With the Abduction of a Brother or Sister, which was written by the siblings of abducted children. This publication is available at www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/217714.pdf.

- Help your other children return to some type of normalcy by going back to school, but listen carefully to them before they go. Request that the school bring counselors into the classroom to discuss the situation with the children, and ask your law enforcement contact to arrange for an officer to go to the school to teach the children both how to recognize dangerous situations and how to get away.

- Extended family members can serve a variety of functions in the search effort — as spokesperson for the family, coordinator of media events, coordinator of volunteers, or coordinator of searchers. They can also help with posters and fliers, request assistance from missing children’s organizations, and gather information to give to law enforcement.

- Don’t try to provide emotional support to everyone in your family. Seek professional counseling for yourself and your children to help you cope.

- Bring callers up to date on the progress of the search by recording simple messages on your home answering machine or voicemail greeting, or Web site.

- Never stop looking. Dedicate part of each day to your missing child by making phone calls, writing letters, contacting law enforcement, or doing whatever you think will help in the search for your missing child.

Checklist: Figuring Out

How To Pay Your Bills

Even though your world has stopped, the rest of the world marches on. If you work outside the home, your boss may be understanding at first, but may tell you later that you will be replaced if your child is not found quickly.

If you are in business for yourself, you will have to balance your need to participate in the search with your need to make decisions about your company.

At some point, you will have to deal with the bills that come in and perhaps other financial concerns as well, even if it’s to buy yourself more time.

Extended leave.

If you need an extended leave from work, ask a family member or friend to talk to your employer on your behalf. For example, some employers allow employees to donate their excess leave time to those who need it.

Extensions on bills.

Talk to mortgage companies, utility companies, and other creditors to see if you can get extensions on your bills.

Re-budgeting.

Ask a friend or an accountant to help you re-budget your finances or refinance your house.

Financial assistance.

Call your state missing children’s clearinghouse to find out if they know of local resources, such as social services or emergency or other financial assistance funds, that might be able to provide short- or long-term support for you.

Victim compensation funds.

Call the Office for Victims of Crime or your state attorney general’s office to find out about victim’s compensation funds. Such funds may cover lost wages and other crime-related expenses.

|

|

| What is a Trigger?, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia | |

View foldable trigger card.

What is a trigger?

Significant anniversaries and dates often remind people of loved ones who are missing but simple daily events can also have similar impacts.

Thoughts, events or objects can trigger feelings that remind you someone is missing. They are usually random and unplanned.

Mistaking a person you see in the street, hearing a song, noticing a particular news story or even smelling a familiar scent can immobilise you and can create an emotional reaction that is difficult to manage.

How can you manage your reaction to triggers?

- Remember that you are not alone; this is a normal response to the unresolved nature of missing.

- No matter how hard you try you cannot always predict when something will remind you of the person you are searching for.

- Give yourself permission to feel the emotion. It can be hard becoming upset away from home but this is a normal reaction.

- Why not try and talk to someone about how you are feeling, like your partner, a friend or a counsellor? Sharing your experiences might help to deal with the pain you are feeling.

|

|

| Are you the parent of a sibling of a missing person?, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia | |

Having a loved one disappear is a harrowing time for the family and friends left behind.

Uncertainty about the health and whereabouts of someone you love can cause enormous challenges on you as an individual as well as on your significant relationships.

In 2005 the Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit (FFMPU) held a roundtable for siblings of missing persons to hear about their unique experiences.

One of the key issues identified by the siblings participating was a concern that their parents may have overlooked or misunderstood the hardship that they also experienced when their brother or sister vanished.

This fact sheet might help you identify ways in which you could support your children as well as an insight into their own journey of unresolved loss.

Common experiences of siblings of missing persons

The reactions of siblings of missing persons included:

- General emotions of fear, anxiety, anger, hopelessness etc.

- Their parents relying heavily on siblings to support them emotionally. In some ways siblings felt that their own emotions were subdued because they did not want to further concern their parents.

- Feeling torn between their parents – some felt that their mothers were outwardly emotional and that their fathers appeared quiet and withdrawn. This led to concerns for their parent’s health and a sense that they could not provide adequate support.

How your experience may differ from that of your children

Some of the siblings spoke about:

- Feeling left out of the investigation process, as parents were often the contact for agencies such as the police. Siblings felt that they may not have been consulted or kept up to date with the case.

- Feeling left out of the support provided by other people – siblings spoke about extended family members and friends asking how their parents were coping and not enquiring about their pain.

- Feeling guilty that their sibling didn’t confide in them before they vanished. Many siblings felt that they should have known what their brother or sister was planning or “seen the signs” prior to their disappearance.

- Feeling that their own successes achieved, after their sibling went missing, were flawed by constant reminders of the absence of their sibling.

- Some siblings spoke about the need to “vanish” by taking extended overseas holidays or relocating to other states. This appeared to provide some respite and distance from the constant reminders that their sibling was missing.

What could you do as a parent to support siblings of missing persons?

- Involve your children and update them about the progress of the investigation.

- If you find this too challenging why not pass the contact details of the investigating officer on to your children so they can make their own enquiries.

- If you feel that you need additional support seek professional assistance or talk to a friend who is in some ways removed from the anguish.

- Understand that the ways in which you cope may differ, either slightly or significantly, from the experience of your children.

- Be aware that your family’s identity is not just a “family of a missing person” that you all have lives where other achievements can also be realised.

|

|

| The SOS Guide: Missing Persons — A Guide for the Families and Friends of Missing Persons, by the National Missing Persons Coordination Centre (NMPCC) | |

Personal health and wellbeing

When a relative or friend is reported missing, the emotional impact on families and friends can be considerable. It’s important to acknowledge that each person may be affected in their own way, and react differently.

Families and friends of missing persons often speak about feelings of fear, anger, guilt, blame, frustration, helplessness, ambiguity, and isolation. While people may not experience all these emotions, it is important to recognise that any of these responses are normal reactions to an extraordinary situation.

Personal health and wellbeing

When someone goes missing it is important to rememberto make some time for yourself and your family. You should consider the following:

- Physical needs: Are you sleeping enough, eating healthy, exercising where possible?

- Emotional needs: Are you experiencing unexpected emotional changes? Do you need to seek professional help, or talk to someone about how you’re feeling/what you’re experiencing? Acknowledging your feelings is important for best management.

- Communicating with others: Are you reaching out to others, accepting support offered, and letting friends and family know how they can help?

- Taking care of each other: Are you talking about your feelings with your family, encouraging children to do the same, and arranging activities with friends, neighbours, relatives or colleagues?

- One day at a time: Are you keeping your routine and making sound decisions? Personal judgement may be affected when making significant life changes. Routine and everyday tasks, can help to remain grounded during unexpected and emotional situations.

If there are children in your family affected by the disappearance of a missing person, notify the children’s school. School counsellors may be a helpful resource in supporting them, and will know what to do in this situation.

You may also find it useful to seek counsel from your General Practitioner. It’s important they understand, however, that the ‘ambiguous’ loss of a missing person is very different to grieving for the loss of someone who has died, where the outcome is known.

When someone goes missing, the uncertainty surrounding what has happened to them, whether they are safe and well, or whether they have met with foul play, can be all-consuming; you may cycle through a range of different feelings each day dependent on what you think has happened to them on any given day.

Writing and remembrance

Finding ways to appropriately remember your missing person can be difficult. Consider visiting a public place of remembrance dedicated to missing persons.

You may also decide to create your own temporary memorial that you can visit or use.

Writing about your experience or keeping a diary can also help, and potentially help others going through a similar experience.

While you may wish to write for therapeutic reasons, you may also want to consider sharing some of your ‘memos’ with newspapers, magazines, or on blogs so that others can better understand the uncertainty surrounding the disappearance of a family member or friend.

Remember: Everyone’s experience is unique. There is no ‘rule book’ when it comes to missing persons, but talking about it can go some way to managing day-to-day activities.

|

|

| Taking care of yourself when someone goes missing, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia | |

It is important to continue to look after yourself

Physical

- Consult your GP if you have any concerns about your physical health and any symptoms you may have. Don’t ignore signs that you may be unwell.

- Try to eat regularly. If you are unable to prepare meals perhaps ask a friend or family member to assist.

- Try to ensure you have some down time and enough sleep. Accept offers of help to allow you time to rest.

- Gentle exercise can help maintain mood and your ability to keep going physically.

Emotional

- Many families describe the ‘emotional roller-coaster’ they experience when someone is missing. Rapid and unexpected emotional changes are not uncommon.

- Acknowledging your feelings is important. This may include talking to someone you trust about what you are going through (for example, a friend, family member, counsellor, your GP) or writing your thoughts and feelings in a journal.

- Give yourself permission to take a break from searching. Breaks may help you to be able to cope in the long run.

- Be kind to yourself and try to do something nice, for example see friends, see a movie, get a massage.

- Feeling distracted and stressed is normal, so take care with activities that require concentration, such as driving.

- Make daily decisions where possible to give you back a feeling of being in control of your life.

- Try to re-establish routine as much as possible.

- Some families explore ways to stay connected emotionally with their missing loved one, for example through rituals such as marking their birthday or visiting a place special to them.

- Be careful of using drugs or alcohol to alleviate pain. Research has shown that many drugs and alcohol can worsen mood and problem solving abilities.

Social

- The experience of missing can feel isolating. Reach out for, and accept support, for example from friends, family, local community groups, and support agencies.

- Let family and friends assist you where possible, for example with child minding, meals, searching, contacting people.

- Let others know what you need for support. Tell them what is helpful or not helpful to say or do.

- People within the same family may react differently. It can be helpful to be understanding and give each other space and permission to cope in their own way.

- Families often ask how they can support children when a loved one goes missing. It can be helpful to: Be honest about what missing means. Let them know that everyone is doing their best to look for the missing person but have not found them yet.

- Notify the children’s school. School counsellors may be a helpful resource in supporting children.

- Set aside time for the children to ask questions and voice their thoughts. It is okay if you do not have answers to all questions.

Financial

- Having someone missing can cause financial strain. You may need to take time off work or the missing person may have contributed to finances.

|

|

| Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief, by Pauline Boss |

Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief, by Pauline Boss, First Edition, 2000, Harvard University Press, 176 pages.

Notice: Unlike everything else on this website, which is free, this book sells for $17.99 on Amazon. It is included here since it is highly recommended by one of Team MibSAR's families that went through an emotionally-exhausting, multyear struggle before they received answers to what happened to their son.

About the Author:

Pauline Boss is Professor of Family Social Science at the University of Minnesota, past President of the National Council on Family Relations, and a psychotherapist in private practice.

Pauline Boss's website.

From the Publisher:

When a loved one dies we mourn our loss. We take comfort in the rituals that mark the passing, and we turn to those around us for support. But what happens when there is no closure, when a family member or a friend who may be still alive is lost to us nonetheless? How, for example, does the mother whose soldier son is missing in action, or the family of an Alzheimer's patient who is suffering from severe dementia, deal with the uncertainty surrounding this kind of loss?

In this sensitive and lucid account, Pauline Boss explains that, all too often, those confronted with such ambiguous loss fluctuate between hope and hopelessness. Suffered too long, these emotions can deaden feeling and make it impossible for people to move on with their lives. Yet the central message of this book is that they can move on. Drawing on her research and clinical experience, Boss suggests strategies that can cushion the pain and help families come to terms with their grief.

Her work features the heartening narratives of those who cope with ambiguous loss and manage to leave their sadness behind, including those who have lost family members to divorce, immigration, adoption, chronic mental illness, and brain injury. With its message of hope, this eloquent book offers guidance and understanding to those struggling to regain their lives.

Contents:

- Frozen grief

- Leaving without goodbye

- Goodbye without leaving

- Mixed emotions

- Ups and downs

- The family gamble

- The turning point

- Making sense out of ambiguity

- The benefit of a doubt

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

|

|

| Missing People: A Guide for Family Members and Service Providers, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales Department of Justice, Australia | |

This is a guide for families dealing with a missing loved one.

Contents:

- Foreword

- Intro-duction

- About missing

- Definition and statistics

- Groups at risk of going missing

- Reasons people go missing

- The needs of families

- When someone is first missing

- How you might feel

- What helps: Looking after yourself when someone is first missing

- How to tell other family members

- Talking to children and young people

- The police investigation

- What to expect

- The search

- Alternative search options

- Non-police tracing services

- Social media and other websites

- The nature of ambiguous loss

- Ambiguous loss

- If missing continues

- Living with ‘not knowing’

- The ongoing focus

- The wheel of thoughts

- The emotional impact

- The nature of grief

- Changes in individual’s core ideas and beliefs

- (alterations in systems of meaning)

- The social impact

- The impact on families

- Changes in relationships

- Community responses to missing

- Access to support

- Sleep difficulties and health changes

- Comments from families on their experience of living with missing

- What can help if missing continues

- Taking care of yourself

- Adjusting expectations you may have of yourself

- Taking time out

- Returning to a routine

- Processing what has happened

- Maintaining relationships

- Maintaining the connection with your missing person

- Support from health professionals and services

- Families and Friends of Missing Persons Groups

- What can help during difficult times

- Raising awareness in the community

- Events for families and friends

- Other issues to consider

- The media

- Legal and financial issues

- The coronial inquest

- Collection of DNA evidence

- The media

- Possible outcomes and issues to consider

- When a missing person is found alive

- When reuniting is not possible

- When a missing person is not found alive

- Messages of hope

- References

- Appendix A: Taking care of yourself when someone goes missing

- Appendix B: Does a work colleague have someone missing?

- Appendix C: FFMPU publications

|

|

| The Disappearance of an Adult in Criminal Circumstances: A Guide Intended for Relatives and Interveners, by Justine Razafindramboa | |

Read pages 3 thru 9.

|

|

| “Unending Not Knowing” — Lack of Resolution and Ambiguous Loss, excerpted from An Uncertain Hope: Missing People’s overview of the theory, research and learning about how it feels for families when a loved one goes missing, by Missing People (MP) in conjunction with Same Cheatle (SANE, Macmillan Cancer Support) |

This excerpt discusses perhaps the biggest emotional challenge of a missing situation for families, the lack of resolution, “the pain of not knowing and the mental torture of perhaps never knowing” (Hunter Institute of Mental Health, 2001).

Missing People hears the agony of this over and over; many family voices echoing fear, confusion and bewilderment. Families feel suspended in this state of pain and uncertainty, unable to move forwards, plan or make life decisions.

This state of being ‘in limbo’ – unable to grieve or to move on – creates a constant desire for answers about the missing person.

|

|

| Living in Limbo The Experiences of, and Impacts on, the Families of Missing People, by Lucy Holmes |

This small scale, exploratory study provides a rich and deep account of the ways in which a disappearance can affect a missing person’s family members.

It identified three key domains of experience faced by the families of missing people:

- emotional and social experiences;

- financial, legal and other practical impacts;

- and experiences with service providers and the media.

Contents:

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Structure of the report

- Structure of the report

- The context of the research

- Missing people

- The impact of going missing on families left behind

- Missing people

- Emotional and social experiences

- Personal experiences

- Family and relationships

- Reactions of friends, colleagues and others

- Perceptions of the disappearance

- The passage of time

- Coping with the loss

- Discussion

- Personal experiences

- Financial, legal and other practical impacts

- The cost of the search

- Losing the missing person’s income

- Dealing with the missing person’s affairs

- Discussion

- The cost of the search

- Experiences with service providers and the media

- The importance of taking action

- Deciding to contact the police

- Experiences with the police

- Confusion about coordination of services

- Missing People

- Media campaigns and appeals

- Discussion

- Summary and recommendations

- Recommendations

- Recommendations

- References

|

|

| A Child is Missing: Providing Support for Families of Missing Children, by Duane T. Bowers, LPC | |

This book was written to assist professionals who may be called upon to assist families with missing children.

Contents:

- Message to the Reader

- Introduction

- A Child Is Missing

- Emotional Shock

- Physical Shock

- Accept the Temporary Absence

- Fill the Roles of the Missing Child

- Review Personal Beliefs About the Status of the Missing Child

- Feel Through the Pain of the Absence, Uncertainty, Fear, and Guilt

- Accept Dual Perceptions of Life

- Create a Long-Term Coping Structure Integrating Both Perceptions

- Assess Your Own Needs

- If a Child Runs Away

- If a Child Is Abducted by a Family Member

- If a Child Is Abducted by a Non-family Member

- Special Needs of Siblings

- Reestablish Structure

- Accept the Temporary Absence

- Fill the Roles of the Missing Child

- Review Personal Beliefs About the Status of the Missing Child

- Feel Through the Pain of the Absence, Uncertainty, Fear, and Guilt

- Create a Long-Term Coping Structure

- Missing or Deceased? Establish a Permanent Relationship With the Sibling

- When a Child Is Recovered

- Additional Thoughts

- Supporting the Spirituality of the Family

- Supporting Friends of the Missing Child

- Supporting Extended Family Members

- Supporting the Person Providing Support

- Supporting the Family Pets

- Appendix A: Resource List

- Appendix B: Reference List

|

|

| An Uncertain Hope: Missing People’s Overview of The Theory, Research and Learning About How it Feels for Families When a Loved One Goes Missing, by Missing People in conjunction with Sam Cheatle (SANE, Macmillan Cancer Support) People (MP) |

This guide is an overview of the currently available research, policy, knowledge, and understanding about what it is really like to cope when someone you love is missing. There isn’t one voice or one experience but there is a shared feeling of desperation and unresolved loss, which is unique to the ‘missing’ issue.

The guide can be used by families, practitioners, and anyone supporting families and friends whilst someone is missing. By summarizing the key information, the guide may make the subject easier to understand. It does contain references for those who wish to read in more depth.

Contents:

- Foreword

- Introduction

- The meaning of missing

- Definitions and numbers

- Why do people go missing?

- What happens to missing people?

- The meaning of missing

- “Unending not knowing” — lack of resolution and ambiguous loss

- “The most distressful of all losses”- exploring the emotional turbulence

- Sources of information

- Feelings in the earlier and the later stages

- Unhappiness, anxiety and despair

- Guilt and self-blame

- Anger and frustration

- Mixed feelings and mood swings

- Hope

- Fear

- Low self-esteem and confused self-perception

- Reduced sense of stability in the world

- A sense of powerlessness

- Searching

- Speculating and questioning

- Physical effects

- Relationships

- Society reactions and status

- Media and the police

- Triggers

- Practical issues15

- How do people cope?

- References

|

|

| In the Loop: Young People Talking About Missing, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales Department of Justice, Australia | |

Contents:

- Foreword

- Intro

- Working with young children

- What is 'Missing?

- How it feels

- Please don't say things like

- What I want from others

- What helps me

- Young people and the right to be included

- Reminders

- Lucy's story

- Information for young people and adults

- Acknowledgments

- References

|

|

| Acknowledging the Empty Space: A Framework to Enhance Support of People Left Behind When Someone is Missing, by Dr Sarah Wayland, Australian Federal Police (AFP) | |

Contents:

- Author

- Acknowl-edgments

- Preface

- Background to the booklet

- Understanding ambiguity in a context of missing people

- What do we need to know about the experience of having someone missing?

- Providing support – guidelines for engagement

- Guidance for counselors responding to families and friends of missing people

- Guidelines for police responding to families and friends of missing people

- Guidance for the community when offering support to families of missing people

- Guidance for the media when working with families of missing people

- Concluding thoughts

- Where to go for more information

- References

- Appendix A: In depth exploration of survey data

|

|

| Families of Missing Adults: Finding Help, by Ontario's Missing Adults (OMA) |

Read pages 16-19 to learn more about support for families with missing loved ones..

|

|

| Missing Kids (MK) |

Owned and operated by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection, MissingKids.ca offers families support in finding their missing child and provides educational materials to help prevent children from going missing.

|

|

| The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System's (NamUs') Victim Services Division |

- peer support network,

- mental health support,

- reunification,

- and outreach and education.

Eric Gonzalez

817.735.5167 eric.gonzalez@unthsc.eduKylie Kelley

817.735.5086

kylie.kelley@unthsc.edu

|

|

| Missing People (MP) |

They also provide specialized support to ease their heartache and confusion. Their free, confidential helpline is available 24 hours a day by phone, text and email 116000@missingpeople.org.uk to support missing children and adults, and their loved ones.

|

|

| Wisconsin Clearinghouse for Missing and Exploited Children and Adults (WCMECA) | |

|

|

| The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) | |

|

|

| The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children's (NCMEC's) Team HOPE | |

They also provide families with access to referrals they may use to help process any emotional or counseling needs.

About Team HOPE:

Team HOPE volunteers are the heart and soul of Team HOPE. They have demonstrated an incredible ability to turn personal tragedies into vital support for other families.

They have volunteers in almost every state and from all walks of life. Volunteers are screened and attend in-depth trainings before they are matched with a family to support. All peer-support is telephone based.

Team HOPE's trained volunteers:

- Help families in crisis with a missing, sexually exploited, or recovered child as they handle the day-to-day issues of coping and/or searching for their child

. - Help provide peer and emotional support, compassion, coping tools, and empowerment to families with missing, sexually exploited, and recovered children.

- Help instill courage, determination, and hope in parents and other family members.

- Help alleviate the feelings of isolation so often resulting from fear and frustration.

|

|

| Jacob Wetterling Resource Center (JWRC) | |

For emotional support during the difficult process of locating a missing child, call 800.325.HOPE or use the form on this JWRC page.

|

|

| The Missing Children Society of Canada | |

The MCSA's Family Support Program provides specialized and comprehensive support for families with missing children.

|

|

| Missing: A Guide for Families and Friends of Individuals with a Mental Illness Who Have Gone Missing, by Christine Lafond, Stephanie Scherbain & Gita Sud, Mental Health Education Resource Centre of Manitoba |

Read page 17 for more information on support for families with missing loved ones.

|

|

| Reconnecting when a missing person is located, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia | |

The role of police

The role of police in a missing person’s case is to ascertain if the missing person is safe and well.

Police need to sight the person before removing them from the missing person’s register. If you are in contact with the missing person and are unsure if police are still searching for them, you, or the missing person, can speak to the officer in charge of the investigation.

In some cases, the missing person does not wish to get back in touch with family and friends when they are found.

If the missing person is an adult, police will respect the privacy of the missing person and will not provide details of their whereabouts without their permission. In this situation, police can only tell families that the person has been sighted.

Police may involve social or health services if the missing person is vulnerable due to age, mental health, or other health reasons.

The emotional response

When a person who has been missing is found you may experience a range of emotions.

People around you might react differently to you. Some people understand that families need to adjust to the discovery of the missing person, while others might expect you to recover as soon as the missing person is located.

For those people who have been missing for a long time, significant events may have occurred while they were away – marriages, divorces, career changes, deaths. It will take some time to explore the impact

of these changes.

The feelings you experience can be confusing and may change over time. This is normal. You may find yourself feeling:

- relieved they are alive;

- happy, excited, anxious, or nervous about seeing them again;

- wanting answers;

- uncertain how to talk with them about what led to them going missing and what happened while they were away;

- worried they may not want contact with you, or fearful they may go missing again;

- angry or hurt that you were left behind to deal with the worry you felt;

- overwhelmed, embarrassed, sad, guilty, insecure, jealous or rejected.

Reconnecting with a missing person

Sometimes the located missing person wishes to reunite with family and friends. Reuniting will depend on many things including the circumstances around them going missing.

It is important to be realistic and open to the changes that may have occurred. Understanding on both sides will be required.

Some things to consider:

- It is helpful to discuss your expectations for reunion as they may vary greatly between individuals.

- Reuniting can take time. Try not to crowd, pressure or rush each other.

- Trust may need to be re-established for reunion to be possible.

- Suggest to the missing person that you would like to hear about their experiences, as well as wanting to share with them what it was like for you.

- If you kept a journal or a scrapbook while your loved one was missing you might like to share parts of it with them. This might help the missing person understand your experience.

- If the missing person does not want to talk to you about things that are concerning them ask them if they would like some support in finding someone else to talk to.

- If you think the person is at risk of going missing again talk about options for them other than to go missing e.g. carrying support numbers in their wallet or identifying a support person they can call to say they are alive and okay.

- If a health issue such as dementia, mental health, or a developmental delay is thought to have contributed to their disappearance, you may need to discuss a safety plan with them, other family members or relevant services.

Counselling or mediation may help with reunion, in dealing with the impact of missing and in the development of safety strategies.

When reunion is not possible

In some instances reunion is not possible. Sometimes the missing person does not wish to or cannot return home due to mental health issues, ongoing conflict or another difficulty.

It can be hard to know what to do in this situation and you may experience feelings of confusion and distress.

Some things to think about:

- You may need to seek advice about whether reunion is possible or appropriate as each circumstance is different.

- It is important to be respectful of the missing person’s request for privacy. Be mindful that continuing to attempt to contact someone against their wishes may push them further away. Providing space and time may benefit the relationship in the long run.

- The person who was missing may be open to staying in contact through other means, including phone, email, or text message, to let you know they are alive and alright. They might agree to such contact without disclosing their whereabouts.

- It can be distressing being separated from a loved family member or friend. You may find you have unanswered questions. Finding a space to talk about this separation with family, friends, or in a counselling environment might be helpful to you.

|

|

| What happens when a missing person is located deceased?, by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia | |

by Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, Victims Services, New South Wales, Department of Justice, Australia, 2012, 2 pages.

Sometimes a missing person is located deceased.

Families and friends may be confronted with a range of distressing emotions and experiences, which can include:

- a loss of hope of seeing the missing person again;

- grief regardless of the length of time the person has been missing;

- disbelief that the missing person has died (even after positive identification);

- relief that, at least, the searching is over;

- reliving emotions experienced when your loved one first went missing;

- being distressed by others’ comments that they are “glad” or “happy” that the missing person has been found;

- feeling isolated when friends appear to move on because the person is no longer missing;

- ongoing questions around the circumstances of the disappearance, what happened and how they died, if these remain unclear;

- concern about media interest;

- being confused about how you are responding to the news of a death versus the way you imagined you might have responded;

- challenges in responding to the different range of conflicting feelings – relief, anger, guilt;

- a feeling of emptiness after the search is over, particularly if this has been a large part of your focus for a long time;

- frustration or confusion if the process of identification of the missing person takes some time.

What might help

Allow yourself time to grieve. Be patient and kind to yourself. Remember there is no right or wrong way to feel at this time. Those around you may respond in different ways. Allow space and understanding for individual differences.

The stress of losing a loved one may take a toll on you physically and emotionally. It is important to take care of yourself by maintaining healthy eating, sleeping, and exercise where possible.

Families sometimes decide on a particular ritual or ceremony to allow an opportunity to acknowledge the person who was missing and to say goodbye. This might be guided by religious, cultural or spiritual beliefs or traditions. Explore these ideas with your family and friends when you feel ready.

Talk about your experience with others. Reach out for, and accept support from friends, family, local community groups and support agencies. Investigate bereavement services that meet your individual needs and circumstances.

Grief support services may be offered as telephone

| << Prior Chapter | Next Chapter >> |

People who say it cannot be done,

should not interrupt those who are doing it.

— Author unknown

If you've been able to read this

Web page...

thank a Teacher;

If you've been able to read this

Web page in English...

thank a Veteran.

— Author unknown

Copyright © 1984-

March 23, 2021

by Michael A. Neiger

Contact Michael Neiger via e-mail at mneiger@hotmail.com

Top

You're here: MibSAR :: M-P Sourcebook Table of Contents :: Support